Family Matters

Issue 26

Family Matters

A Closer Look at Frank Bowling’s

Middle Passage Paintings

Grace Aneiza Ali

Introduction

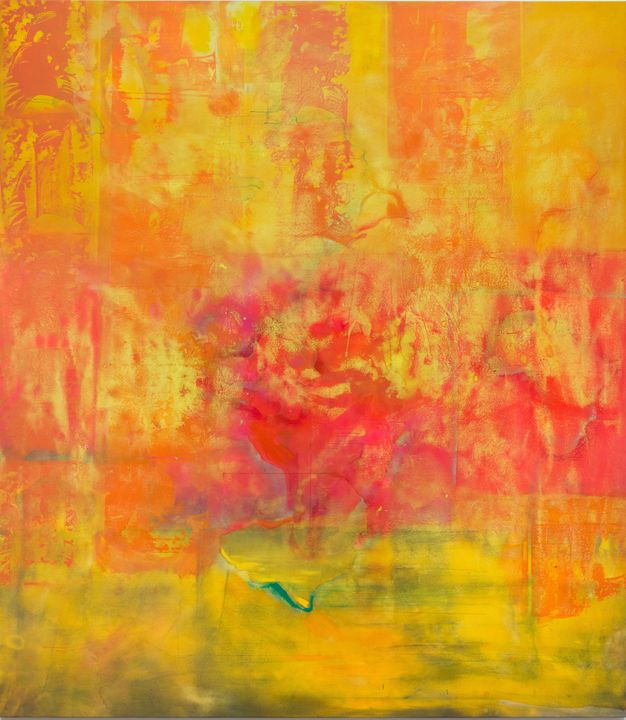

In 1970 Frank Bowling, who was born in 1934 in British Guiana (now Guyana), produced two large-scale paintings in his New York City studio evocatively titled Middle Passage (figs. 1 and 2).1 Though distinct in their color abstractions and compositions, both paintings featured images of the artist’s family. Invoking the transatlantic histories that informed his Caribbean identity, Bowling remarked:

I named the painting Middle Passage because I am a product of the Middle Passage.

But . . . I do not bring my images together because of the history and brutality of that terrible crossing, but rather in spite of it.2

In this brief but revealing statement, Bowling calls attention to a critical artistic gesture happening beyond the canvas: the act of naming—the intentional language of the title. The only overt signal that the painting is about the Middle Passage is in the title. In this gesture, we are invited to ask the question What work is the title tasked to do that the painting isn’t?

The statement also reflects what Bowling is not doing. He is not embedding his images, by which he means photographs of his family and his mother’s house, because of the brutality of the Middle Passage. In these words of defiance, the declaration that the paintings exist in the world “in spite of” the Middle Passage, lies an explicit refusal: although one is a product of a great terror, one is not authored by it.

1Bowling first arrived in London in 1953. He relocated to New York City in 1966 and returned to London in 1975. He went on to divide his time between London and New York, maintaining studios in both cities.

Bowling interview, in Charles Childs, “Larry Ocean Swims the Nile, Mississippi and Other Rivers”, in Some American History (Houston, TX: Rice University, 1971), exhibition catalogue, 19.

Turner’s The Slave Ship

Scholars have pointed to how Bowling’s use of color in the first Middle Passage painting—the striking yellows and reds and blazing oranges and saffrons—are in dialogue with J.M.W. Turner’s reds and yellows in his renowned painting The Slave Ship (1840) (fig. 3).3 The art historian Dorothy Price aptly notes:

[Bowling’s “Middle Passage”] becomes an alternative memorial to the traumas enacted through the barbaric trade in enslaved African people via its layering and haunting cartography and colouristic abstraction. Bowling’s dramatic combination of fiery color is a major reworking of Turner’s sunset.4

Similarly in the second Middle Passage painting, Bowling’s use of red, black, yellow, white, and green has been read as an allusion to the colors of the flag of Bowling’s native country, Guyana.

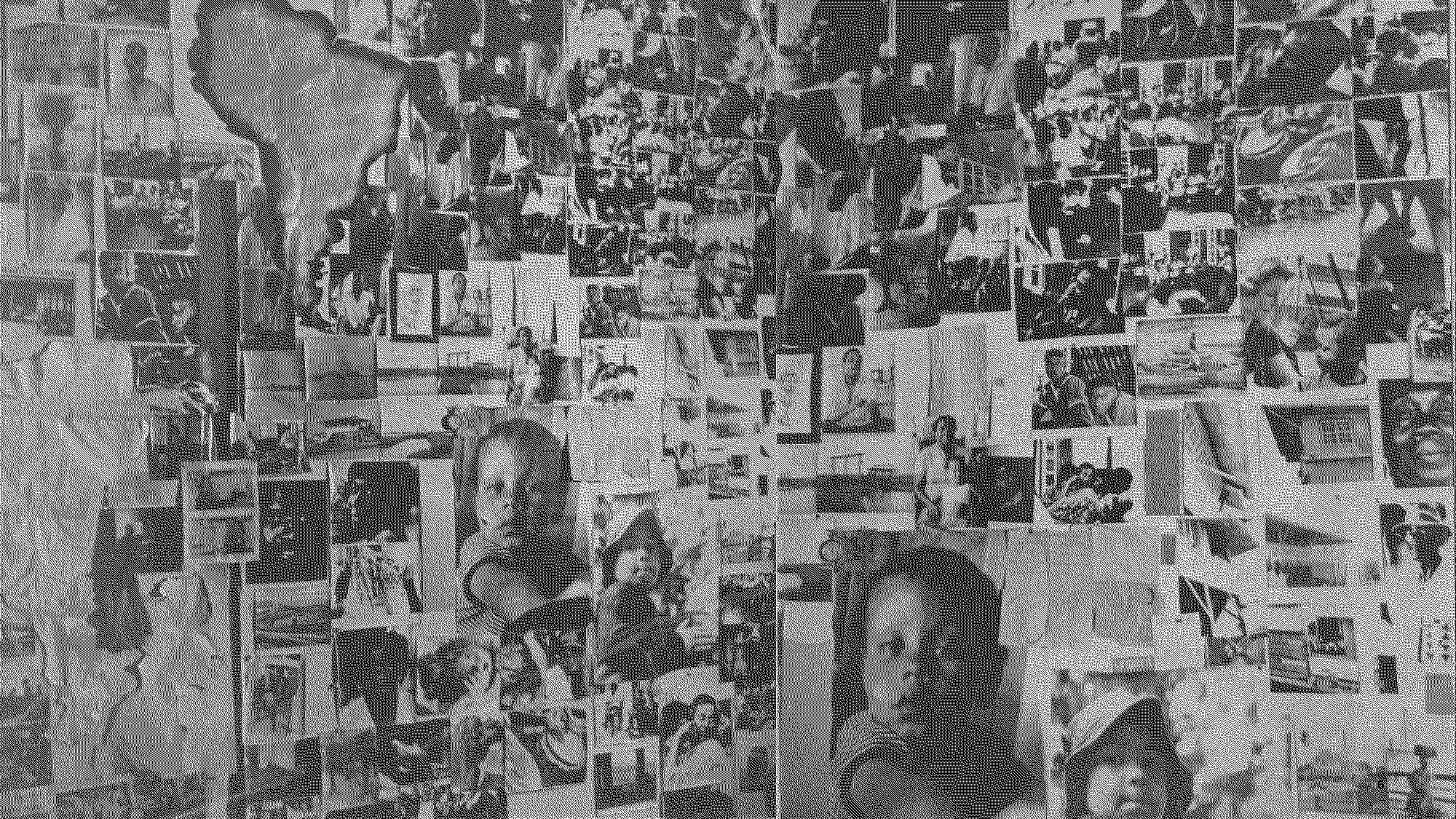

Underneath the painting’s firestorm of color, Bowling embeds photographs of his family, rendering some more visible than others. By design, they require some detective work. Not only is Bowling a master of color and abstraction, but the artist is a master coder as well.

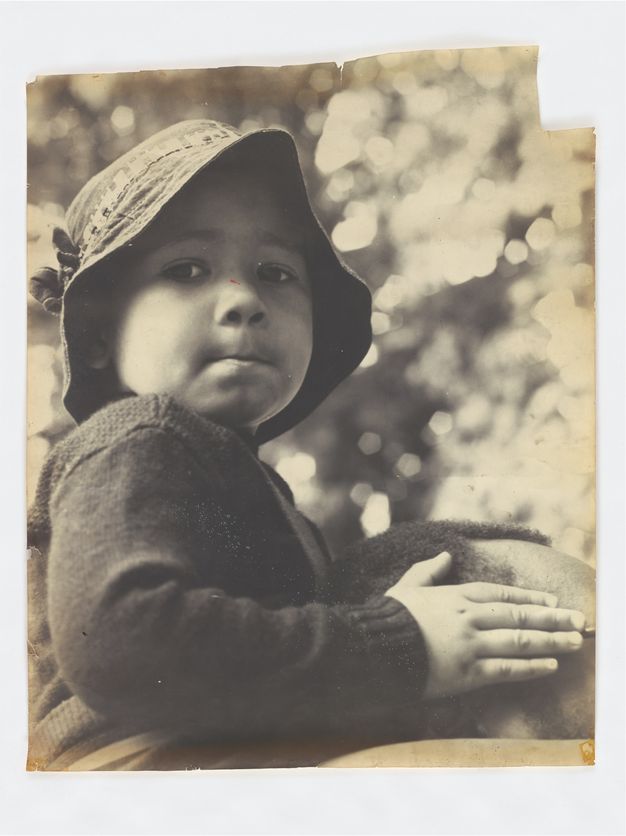

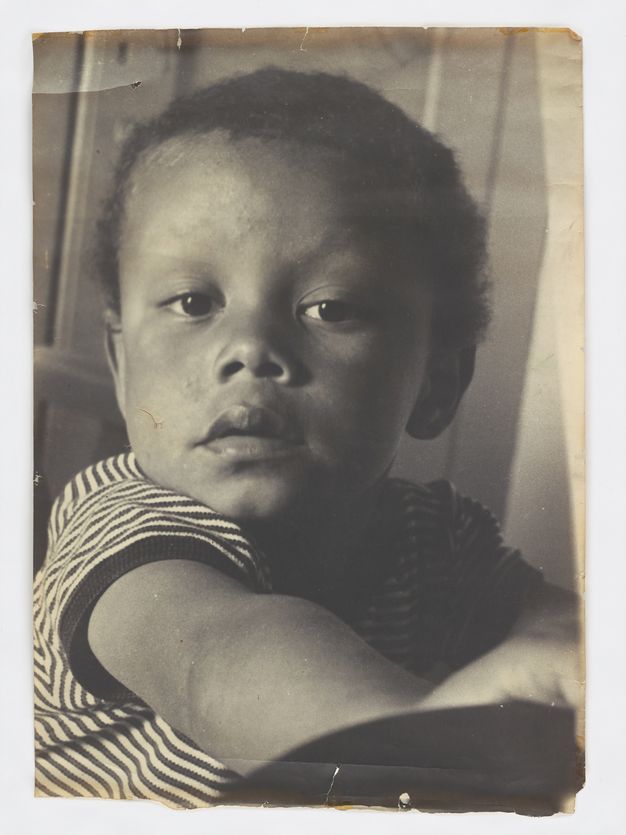

In the first Middle Passage painting, Bowling makes his sons the painting’s most visible protagonists. Beginning with the top section, the artist silkscreens photographic prints of his eldest and youngest sons, Sacha and Dan Bowling, taken in 1960s London (figs. 4 and 5). Becoming fainter and less visible as you move down the composition, these images are repeated over and over again until they disappear into the canvas via Bowling’s intensive layering and overpainting.

In addition to the photographs of his sons, embedded in the painting is another image taken in Guyana of two boatmen who worked the ferry crossing the Berbice River, a major river that enters the Atlantic Ocean at New Amsterdam, Bowling’s hometown. One of the men was a relative.5 The image’s presence cannot be detected. But that is intentional, as Bowling often labors toward erasure. The Middle Passage is haunted by another obscured artistic gesture—a ghosted photograph of boatmen in proximity to the Atlantic—to usher in another symbol of that “terrible crossing”.

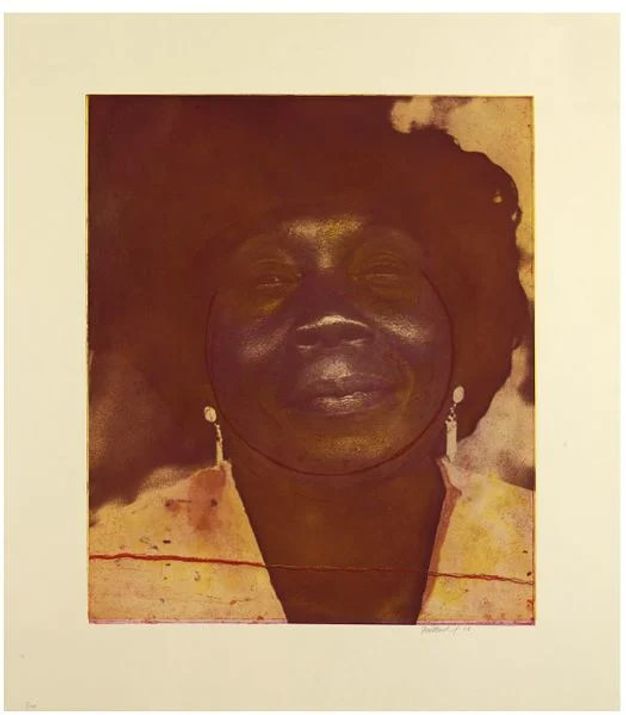

At the top of the painting, Bowling inserts an image of his family’s house in New Amsterdam, British Guiana, which he called “mother’s house”.6 It is repeated to various degrees of legibility in the top half of the painting. At the center are silkscreened prints of a photograph of his mother, Agatha Bowling, repeated multiple times, sometimes faintly, sometimes obscured, but always present and central. With the insertion of photographs taken in Guyana and the use of the colors of the Guyanese flag, this Middle Passage painting, more so than the first, is an overt call back to Guyana.

Both Middle Passage paintings illustrate the precursor to Bowling’s later series of Map Paintings. The first version shows drifting, floating, and ghostly outlines of the contours of Africa, South America, and Australia. At times, as with the continent of Africa, the maps are skewed and turned on their side.

In the second Middle Passage, the outlines of South America and Guyana are present. Stenciled letters spelling out “Guyana” appear above the rectangular strip of white at the left. As a young boy in school in New Amsterdam, Bowling had to learn how to draw the map of Guyana by hand. That lived experience is evident toward the painting’s bottom corners where two outlines of the map of Guyana are layered onto the silkscreen prints of his sons.

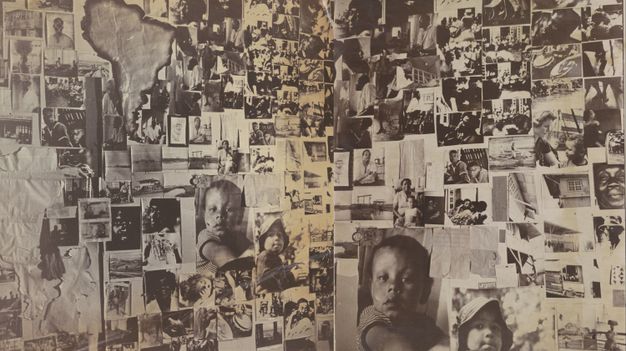

These images, connecting generations (Bowling’s sons, mother, and relatives), geographies (photographs of his family home in British Guiana and family photos taken between London and New Amsterdam), and stencil outlines of maps of Africa, South America, and Guyana were part of a bounty of reference material prominently on view on the wall of Bowling’s New York studio in the late 1960s and early 1970s (fig. 11).

How then can we read the family tree Bowling charts in the context of the Middle Passage?

We’ve borne witness to the devastating ways in which slavery was systematically designed to dismantle the Black family—physically, psychologically, generationally. We continue to bear witness to the ways in which modern migration separates and ruptures families. Against this backdrop, Bowling chooses mapmaking and world-building. He presents in the Middle Passage paintings a genealogical chart not with family names but with family images. He makes visible an interconnected family, charting a continuum across generations and geographies.

Bowling counters the Middle Passage and migration’s ruptures with lineage and legacy. The family is present in spite of systems meant to tear apart, break down, and separate.

“It was all part of my attempt to break down and away from the Guyana preoccupation, you know colonial stuff? It’s a mixture of maps and money and family. My relatives, my sons, my mother. It’s full of reference. ‘Middle Passage’ was the Atlantic right? They brought all these people in chains in the holds of boats. Middle Passage was this dangerous journey. Anyone who survived Middle Passage had to be very, very strong. I was trying to jump out of the trick bag that I was being forced into. I was always trying to destroy, erase, and reconstitute cliches, about things like the ‘Middle Passage’”.7

Bowling’s artistic gestures “to destroy, erase, and reconstitute cliches” crack open questions about what is absent in the painting. Instead of representing the visceral brutality of that terrible crossing, he shirks Middle Passage iconography—there is no slave ship, no tightly packed bowels, no perilous sea with drowning bodies, no shackles, no brutalities, no horrors and indignities.

Bowling’s refusal to represent the Middle Passage in ways that are legible is in conversation with what the scholar Sadiya Hartman asks as she labors in the archives of slavery: “How does one tell impossible stories?”8 We must do two things simultaneously, she says: “tell an impossible story and amplify the impossibility of its telling”.9

7Bowling, unpublished interview with Anna Schneider in his studio at Peacock Yard, London, February 1, 2017, cited in Enwenzor, Mappa Mundi, 33.

Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts”, Small Axe: A Journal of Criticism 12, no. 2 (June 2008): 10.

Ibid., 11.

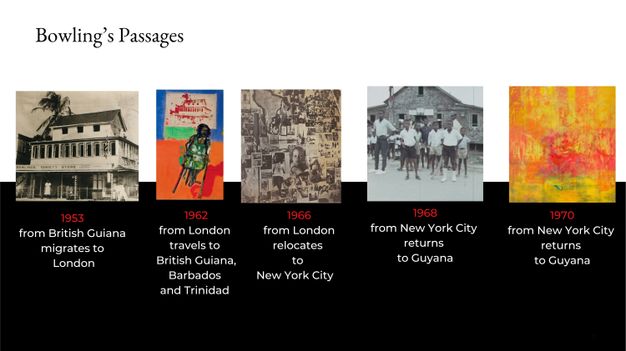

In 1953, at 19 years of age, Bowling left British Guiana for London. He returned to Guyana three times between 1962 and 1970, each return leaving an indelible mark on his psyche and his work.

The word “passage” (the act of moving through one place to another) connotes migration. In naming his 1992 seminal poetry collection Middle Passages —in the plural—the Barbadian poet Kamau Brathwaite (1930–2020), Bowling’s contemporary, illuminated a global backdrop of multiple migrations taking place throughout the Black diaspora across time and space.10 Indeed, the timeline from when Bowling first left British Guiana in 1953 to when he produced the Middle Passage paintings in 1970 parallels the artist’s own transatlantic passages through the Caribbean (Guyana, Barbados, Trinidad), London, and New York. It is a timeline that reflects Bowling’s migrant self. Of his engagement with the ancestral, historical, and contemporary passages coding his work, Bowling noted, “My pictures were concerned with map making, and an attempt by me, to understand my personal and historical journey across the Middle Passage”.11

One of those critical passages was Bowling’s multiple returns to Guyana. It was his 1968 trip to New Amsterdam, just two years after the country gained independence from British rule, that yielded several of the photographs Bowling used in the Middle Passage paintings: the portrait of his mother, the photograph of the family’s house, and the hidden image of the boatmen in New Amsterdam. During this 1968 trip Bowling was also making a film about his life in the town of New Amsterdam, shooting hours of 16 mm footage (fig. 13).12

Bowling has said of his young days growing up in New Amsterdam:

[I]t is the most important place, and it reappears all the time. . . . In my quiet moments it reappears. It was a town that was full of terror, and at the same time it was marvelous. . . . It belonged to me.13

The terror Bowling speaks of took in many forms—it was the terror of colonial violence, racism, ethnic divisions, segregation, and disenfranchisement under the iron fist of colonial rule. It was a terror turned to anger for the entrenched poverty of what was then, and remains, one of the poorest countries in the region.

Guyana today continues to grapple with a colonial afterlife. The aftermath of decades of migration has left the country with one of the world’s highest migration rates. And, of those who remain, fewer than 3 percent are college educated and nearly half live below the poverty line. In the Guyana into which Bowling was born, there was no advancing beyond secondary school, and at the time of this 1968 footage there was no university in Guyana. For the young boys on the streets of New Amsterdam shown in the video clip—boys who are a reflection of the artist himself in his childhood—the remnants of the Middle Passage and a migration exodus left Guyana as a land of dreams deferred.

13Frank Bowling, “Interview by Mel Gooding”, in Frank Bowling, ed. Mel Gooding (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2011), exhibition catalogue, 15.

One Continent/To Another

(extracts)

Child of the middle passage womb

push

daughter of a vengeful Chi

she came

into the new world

birth aching her pain

from one continent/to another…

But being born a woman

she moved again

knew it was the Black Beginning

though everything said it was

the end…

Now she stoops

in green canefields

piecing the life she would lead

---- Grace Nichols, I Is a Long Memoried Woman.

The Middle Passage signals death. Yet Bowling charted new beginnings and new generations to imagine a future both free from—and in spite of—his generational and contemporary terrors. In Glissant and the Middle Passage, John Drabinski similarly notes: “The Middle Passage has no representation. Rather, the Middle Passage is simultaneously the evacuation of meaning and the beginning of being, becoming, knowing, and thinking”.14

This notion of the Middle Passage as the “beginning of being” is the thesis of the poem “One Continent / To Another” by another contemporary of Bowling’s, the Guyanese-British poet Grace Nichols (fig. 14). In this poignant pairing with Bowling’s Middle Passage paintings, Nichols also sees herself “as child of the middle passage”.15 However, in a later stanza Nichols writes her explicit refusal and, to borrow Bowling’s words, authors a new beginning in spite of the great terror of the Middle Passage.

14John E. Drabinski, Glissant and the Middle Passage: Philosophy, Beginning, Abyss (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019), x.

Grace Nichols, “One Continent/To Another”, in I Is a Long Memoried Woman (London: Karnak House, 1983), 5–7.

Acknowledgements

My gratitude to Sir Frank Bowling and Ben Bowling for their boundless generosity and to Nastasia Alberti and the entire staff of the Frank Bowling Archive and the Frank Bowling Studio for supporting this research. This essay has been adapted from a talk given at the Royal Academy of Arts on April 26, 2024 on the occasion of the “Art, Colonialism and Change” symposium in response to the exhibition Entangled Pasts, 1768–Now: Art, Colonialism and Change. My thanks to Professor Dorothy Price (and the exhibition’s curatorial team) for her important scholarship and the invitation to speak about Bowling’s Middle Passage paintings. My research on Frank Bowling was generously supported by a Paul Mellon Centre Curatorial Research Grant and I express my gratitude to Dr. Sarah Victoria Turner, Baillie Card, Maisoon Rehani and Jacqueline Harvey for their editorial expertise and care with this feature.

About the author

-

Grace Aneiza Ali is a Guyanese-born curator and assistant professor in the Department of Art and Art History at Florida State University and affiliated faculty in the Native American and Indigenous Studies (NAIS) Center. She is also a 2024–25 Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fellow at The Huntington in Los Angeles, California. As a curator-scholar of contemporary art of the Global South, her curatorial research practice examines the conceptual links and slippages at the nexus of art and migration. Ali specializes in art of the Caribbean diaspora with particular attention to her homeland, Guyana. Her book* Liminal Spaces: Migration and Women of the Guyanese Diaspora* explores the art and migration narratives of women of Guyanese heritage. Ali is editor in chief of the College Art Association’s *Art Journal Open *and a member of the board of advisors for British Art Studies.

Footnotes

-

1

Bowling first arrived in London in 1953. He relocated to New York City in 1966 and returned to London in 1975. He went on to divide his time between London and New York, maintaining studios in both cities. ↩︎

-

2

Bowling interview, in Charles Childs, “Larry Ocean Swims the Nile, Mississippi and Other Rivers”, in Some American History (Houston, TX: Rice University, 1971), exhibition catalogue, 19. ↩︎

-

3

The Slave Ship[, originally titled] Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying—Typhoon Coming On[,] [by British artist] J.M.W. Turner was [first exhibited at] the Royal Academy of Arts [in 1840.] ↩︎

-

4

Dorothy Price, “Fallacies of Hope”, in Entangled Pasts, 1768–Now: Art, Colonialism and Change (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2004), exhibition catalogue, 43. ↩︎

-

5

Okwui Enwenzor, “Mappa Mundi: Frank Bowling’s Cognitive Abstraction”, in Mappa Mundi (Munich: Haus der Kunst, 2017), 33. ↩︎

-

6

For more on Bowling’s “mother’s house paintings”, see Grace Aneiza Ali’s research seminar, “Frank Bowling: The Mother’s House Paintings” at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, February 7, 2024, YouTube video, 1:16:34, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=53lkQJB5jrk. ↩︎

-

7

Bowling, unpublished interview with Anna Schneider in his studio at Peacock Yard, London, February 1, 2017, cited in Enwenzor, Mappa Mundi, 33. ↩︎

-

8

Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts”, Small Axe: A Journal of Criticism 12, no. 2 (June 2008): 10. ↩︎

-

9

Ibid., 11. ↩︎

-

10

Kamau Brathwaite, Middle Passages (Newcastle upon Tyne: Bloodaxe Books, 1992). ↩︎

-

11

Frank Bowling, “Some Notes towards an Exhibition of African American Abstract Art”, in The Search for Freedom: African American Abstract Painting 1945–1975 (New York: Kenkeleba House, 1991), 126. ↩︎

-

12

Bowling traveled to Guyana with the photographer Tina Tranter, who filmed the footage. ↩︎

-

13

Frank Bowling, “Interview by Mel Gooding”, in Frank Bowling, ed. Mel Gooding (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2011), exhibition catalogue, 15. ↩︎

-

14

John E. Drabinski, Glissant and the Middle Passage: Philosophy, Beginning, Abyss (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019), x. ↩︎

-

15

Grace Nichols, “One Continent/To Another”, in I Is a Long Memoried Woman (London: Karnak House, 1983), 5–7. ↩︎

Bibliography

Ali, Grace Aneiza. “Frank Bowling: The Mother’s House Paintings”. Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, Research Seminar, February 7, 2024. YouTube video, 1:16:34. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=53lkQJB5jrk.

Bowling, Frank. “Interview by Mel Gooding”. In Frank Bowling, edited by Mel Gooding, 13–37. London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2011.

Bowling, Frank. “Some Notes towards an Exhibition of African American Abstract Art”. In The Search for Freedom: African American Abstract Painting 1945–1975. New York: Kenkeleba House, 1991. https://frankbowling.blogspot.com/1991/01/some-notes-towards-exhibition-of.html.

Brathwaite, Kamau. Middle Passages. Newcastle upon Tyne: Bloodaxe Books, 1992.

Childs, Charles. “Larry Ocean Swims the Nile, Mississippi and Other Rivers”. In Some American History. Houston, TX: Institute for the Arts, Rice University, 1971. Exhibition catalogue: Art Gallery, Rice University.

Drabinski, John E. Glissant and the Middle Passage: Philosophy, Beginning, Abyss. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019.

Enwenzor, Okwui. “Mappa Mundi: Frank Bowling’s Cognitive Abstraction”. In Mappa Mundi, 16–45. Munich: Haus der Kunst, 2017.

Hartman, Saidiya. “Venus in Two Acts”. Small Axe: A Journal of Criticism 12, no. 2 (June 2008): 1–14.

Nichols, Grace. “One Continent / To Another”. In I Is a Long Memoried Woman, 5–7. London: Karnak House, 1983.

Price, Dorothy. “Fallacies of Hope”. In Entangled Pasts, 1768–Now: Art, Colonialism and Change, 39–45. London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2004. Exhibition catalogue: Royal Academy of Arts, London.

Imprint

| Author | Grace Aneiza Ali |

|---|---|

| Date | 29 May 2025 |

| Category | Look first |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Editorial Group) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-26/editorial |

| Cite as | Ali, Grace Aneiza. “Family Matters: A Closer Look at Frank Bowling’s Middle Passage Paintings.” In British Art Studies. London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale Center for British Art, 2025. https://bas-journal-framework.netlify.app/issues/26/frank-bowling-middle-passage-paintings/. |